And still watching movies. I just finished the best movie. It's my first Ozu film, Tokyo Story.

It had been recommended to me, indirectly, as something I might want to see for it's minimalistic visual style in relation to Too Marvelous, which I intend to shoot very simply. But Tokyo Story is a great movie. Me and the wife had, like, a 20-minute discussion after it. It's just real. It was shot very well, but what really got me was the story and how accurately it depicts the loneliness of getting old, of raising children who have forgotten you, of the disappointment often reciprocated between parents and their adult children. For it to be a 55 year old Japanese film, it dealt with some highly contemporary themes, ageless themes, in fact. I had heard Ozu was a beast before, but now I'm gonna have to get involved (c) Raphael Saadiq.

Some other recent discoveries (and rediscoveries) that I plan to implement: Kramer .vs Kramer's look, period. That film is so natural. I watched it again a couple weeks ago online via Netflix. Barry Lyndon's au naturale lighting was kind of gutsy for a period piece in retrospect and much up my alley for this project. I just watched Talk to Her yesterday (Habla con Ella por mi amigos espanol) and loved the way Almodovar found a way to make multiple hospital scenes each look interesting. (Yes, my script has multiple hospital scenes. But it does not, unfortunately, have Paz Vega.)

I'll be off work Thursday and Friday to make some calls and take care of some other, more practical business. I've bought some tickets lately, for two shows, that I'm amped about: Sly and the Family Stone in Anaheim on Friday night and the Prince .vs Michael Soulslam in Glendale w/ DJ Spinna on May 2.

You know I'll have the pics and stuff, either here or on MySpace. Just keeping you posted. Holla at your boy.

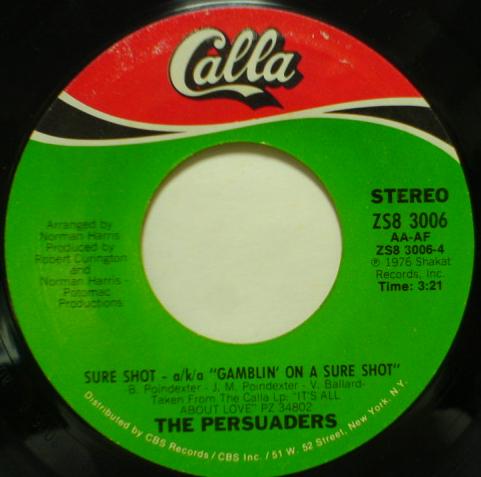

Musically: rediscovered Beck's Guero and The Information today, as well as Alice Russell's My Favourite Letters. And you need to kill for The Persuaders' "Sureshot."

HAPPY BIRTHDAY MAMA!!!!!!!!!!!